Let me preface this with an apology: this is a technology love story, and as such, it’s long, rambling, sentimental and personal. Also befitting a love story, it has a When Harry Met Sally feel to it, in that its origins are inauspicious…

First encounters

Over a decade ago, I worked on a technology to which a competitor paid the highest possible compliment: they tried to implement their own knockoff. Because this was done in the open (and because it is uniquely mesmerizing to watch one’s own work mimicked), I spent way too much time following their mailing list and tracking their progress (and yes, taking an especially shameful delight in their occasional feuds). On their team, there was one technologist who was clearly exceptionally capable — and I confess to being relieved when he chose to leave the team relatively early in the project’s life. This was all in 2005; for years for me, Rust was “that thing that Graydon disappeared to go work on.” From the description as I read it at the time, Graydon’s new project seemed outrageously ambitious — and I assumed that little would ever come of it, though certainly not for lack of ability or effort…

Fast forward eight years to 2013 or so. Impressively, Graydon’s Rust was not only still alive, but it had gathered a community and was getting quite a bit of attention — enough to merit a serious look. There seemed to be some very intriguing ideas, but any budding interest that I might have had frankly withered when I learned that Rust had adopted the M:N threading model — including its more baroque consequences like segmented stacks. In my experience, every system that has adopted the M:N model has lived to regret it — and it was unfortunate to have a promising new system appear to be ignorant of the scarred shoulders that it could otherwise stand upon. For me, the implications were larger than this single decision: I was concerned that it may be indicative of a deeper malaise that would make Rust a poor fit for the infrastructure software that I like to write. So while impressed that Rust’s ambitious vision was coming to any sort of fruition at all, I decided that Rust wasn’t for me personally — and I didn’t think much more about it…

Some time later, a truly amazing thing happened: Rust ripped it out. Rust’s reasoning for removing segmented stacks is a concise but thorough damnation; their rationale for removing M:N is clear-eyed, thoughtful and reflective — but also unequivocal in its resolve. Suddenly, Rust became very interesting: all systems make mistakes, but few muster the courage to rectify them; on that basis alone, Rust became a project worthy of close attention.

So several years later, in 2015, it was with great interest that I learned that Adam started experimenting with Rust. On first read of Adam’s blog entry, I assumed he would end what appeared to be excruciating pain by deleting the Rust compiler from his computer (if not by moving to a commune in Vermont) — but Adam surprised me when he ended up being very positive about Rust, despite his rough experiences. In particular, Adam hailed the important new ideas like the ownership model — and explicitly hoped that his experience would serve as a warning to others to approach the language in a different way.

In the years since, Rust continued to mature and my curiosity (and I daresay, that of many software engineers) has steadily intensified: the more I have discovered, the more intrigued I have become. This interest has coincided with my personal quest to find a programming language for the back half of my career: as I mentioned in my Node Summit 2017 talk on platform as a reflection of values, I have been searching for a language that reflects my personal engineering values around robustness and performance. These values reflect a deeper sense within me: that software can be permanent — that software’s unique duality as both information and machine afford a timeless perfection and utility that stand apart from other human endeavor. In this regard, I have believed (and continue to believe) that we are living in a Golden Age of software, one that will produce artifacts that will endure for generations. Of course, it can be hard to hold such heady thoughts when we seem to be up to our armpits in vendored flotsam, flooded by sloppy abstractions hastily implemented. Among current languages, only Rust seems to share this aspiration for permanence, with a perspective that is decidedly larger than itself.

Taking the plunge

So I have been actively looking for an opportunity to dive into Rust in earnest, and earlier this year, one presented itself: for a while, I have been working on a new mechanism for system visualization that I dubbed statemaps. The software for rendering statemaps needs to inhale a data stream, coalesce it down to a reasonable size, and render it as a dynamic image that can be manipulated by the user. This originally started off as being written in node.js, but performance became a problem (especially for larger data sets) and I did what we at Joyent have done in such situations: I rewrote the hot loop in C, and then dropped that into a node.js add-on (allowing the SVG-rendering code to remain in JavaScript). This was fine, but painful: the C was straightforward, but the glue code to bridge into node.js was every bit as capricious, tedious, and error-prone as it has always been. Given the performance constraint, the desire for the power of a higher level language, and the experimental nature of the software, statemaps made for an excellent candidate to reimplement in Rust; my intensifying curiosity could finally be sated!

As I set out, I had the advantage of having watched (if from afar) many others have their first encounters with Rust. And if those years of being a Rust looky-loo taught me anything, it’s that the early days can be like the first days of snowboarding or windsurfing: lots of painful falling down! So I took deliberate approach with Rust: rather than do what one is wont to do when learning a new language and tinker a program into existence, I really sat down to learn Rust. This is frankly my bias anyway (I always look for the first principles of a creation, as explained by its creators), but with Rust, I went further: not only did I buy the canonical reference (The Rust Programming Language by Steve Klabnik, Carol Nichols and community contributors), I also bought an O’Reilly book with a bit more narrative (Programming Rust by Jim Blandy and Jason Orendorff). And with this latter book, I did something that I haven’t done since cribbing BASIC programs from Enter magazine back in the day: I typed in the example program in the introductory chapters. I found this to be very valuable: it got the fingers and the brain warmed up while still absorbing Rust’s new ideas — and debugging my inevitable transcription errors allowed me to get some understanding of what it was that I was typing. At the end was something that actually did something, and (importantly), by working with a program that was already correct, I was able to painlessly feel some of the tremendous promise of Rust.

Encouraged by these early (if gentle) experiences, I dove into my statemap rewrite. It took a little while (and yes, I had some altercations with the borrow checker!), but I’m almost shocked about how happy I am with the rewrite of statemaps in Rust. Because I know that many are in the shoes I occupied just a short while ago (namely, intensely wondering about Rust, but also wary of its learning curve — and concerned about the investment of time and energy that climbing it will necessitate), I would like to expand on some of the things that I love about Rust other than the ownership model. This isn’t because I don’t love the ownership model (I absolutely do) or that the ownership model isn’t core to Rust (it is rightfully thought of as Rust’s epicenter), but because I think its sheer magnitude sometimes dwarfs other attributes of Rust — attributes that I find very compelling! In a way, I am writing this for my past self — because if I have one regret about Rust, it’s that I didn’t see beyond the ownership model to learn it earlier.

I will discuss these attributes in roughly the order I discovered them with the (obvious?) caveat that this shouldn’t be considered authoritative; I’m still very much new to Rust, and my apologies in advance for any technical details that I get wrong!

1. Rust’s error handling is beautiful

The first thing that really struck me about Rust was its beautiful error handling — but to appreciate why it so resonated with me requires some additional context. Despite its obvious importance, error handling is something we haven’t really gotten right in systems software. For example, as Dave Pacheo observed with respect to node.js, we often conflate different kinds of errors — namely, programmatic errors (i.e., my program is broken because of a logic error) with operational errors (i.e., an error condition external to my program has occurred and it affects my operation). In C, this conflation is unusual, but you see it with the infamous SIGSEGV signal handler that has been known to sneak into more than one undergraduate project moments before a deadline to deal with an otherwise undebuggable condition. In the Java world, this is slightly more common with the (frowned upon) behavior of catching java.lang.NullPointerException or otherwise trying to drive on in light of clearly broken logic. And in the JavaScript world, this conflation is commonplace — and underlies one of the most serious objections to promises.

Beyond the ontological confusion, error handling suffers from an infamous mechanical problem: for a function that may return a value but may also fail, how is the caller to delineate the two conditions? (This is known as the semipredicate problem after a Lisp construct that suffers from it.) C handles this as it handles so many things: by leaving it to the programmer to figure out their own (bad) convention. Some use sentinel values (e.g., Linux system calls cleave the return space in two and use negative values to denote the error condition); some return defined values on success and failure and then set an orthogonal error code; and of course, some just silently eat errors entirely (or even worse).

C++ and Java (and many other languages before them) tried to solve this with the notion of exceptions. I do not like exceptions: for reasons not dissimilar to Dijkstra’s in his famous admonition against “goto”, I consider exceptions harmful. While they are perhaps convenient from a function signature perspective, exceptions allow errors to wait in ambush, deep in the tall grass of implicit dependencies. When the error strikes, higher-level software may well not know what hit it, let alone from whom — and suddenly an operational error has become a programmatic one. (Java tries to mitigate this sneak attack with checked exceptions, but while well-intentioned, they have serious flaws in practice.) In this regard, exceptions are a concrete example of trading the speed of developing software with its long-term operability. One of our deepest, most fundamental problems as a craft is that we have enshrined “velocity” above all else, willfully blinding ourselves to the long-term consequences of gimcrack software. Exceptions optimize for the developer by allowing them to pretend that errors are someone else’s problem — or perhaps that they just won’t happen at all.

Fortunately, exceptions aren’t the only way to solve this, and other languages take other approaches. Closure-heavy languages like JavaScript afford environments like node.js the luxury of passing an error as an argument — but this argument can be ignored or otherwise abused (and it’s untyped regardless), making this solution far from perfect. And Go uses its support for multiple return values to (by convention) return both a result and an error value. While this approach is certainly an improvement over C, it is also noisy, repetitive and error-prone.

By contrast, Rust takes an approach that is unique among systems-oriented languages: leveraging first algebraic data types — whereby a thing can be exactly one of an enumerated list of types and the programmer is required to be explicit about its type to manipulate it — and then combining it with its support for parameterized types. Together, this allows functions to return one thing that’s one of two types: one type that denotes success and one that denotes failure. The caller can then pattern match on the type of what has been returned: if it’s of the success type, it can get at the underlying thing (by unwrapping it), and if it’s of the error type, it can get at the underlying error and either handle it, propagate it, or improve upon it (by adding additional context) and propagating it. What it cannot do (or at least, cannot do implicitly) is simply ignore it: it has to deal with it explicitly, one way or the other. (For all of the details, see Recoverable Errors with Result.)

To make this concrete, in Rust you end up with code that looks like this:

fn do_it(filename: &str) -> Result {

let stat = match fs::metadata(filename) {

Ok(result) => { result },

Err(err) => { return Err(err); }

};

let file = match File::open(filename) {

Ok(result) => { result },

Err(err) => { return Err(err); }

};

/* ... */

Ok(())

}

Already, this is pretty good: it’s cleaner and more robust than multiple return values, return sentinels and exceptions — in part because the type system helps you get this correct. But it’s also verbose, so Rust takes it one step further by introducing the propagation operator: if your function returns a Result, when you call a function that itself returns a Result, you can append a question mark on the call to the function denoting that upon Ok, the result should be unwrapped and the expression becomes the unwrapped thing — and upon Err the error should be returned (and therefore propagated). This is easier seen than explained! Using the propagation operator turns our above example into this:

fn do_it_better(filename: &str) -> Result {

let stat = fs::metadata(filename)?;

let file = File::open(filename)?;

/* ... */

Ok(())

}

This, to me, is beautiful: it is robust; it is readable; it is not magic. And it is safe in that the compiler helps us arrive at this and then prevents us from straying from it.

Platforms reflect their values, and I daresay the propagation operator is an embodiment of Rust’s: balancing elegance and expressiveness with robustness and performance. This balance is reflected in a mantra that one hears frequently in the Rust community: “we can have nice things.” Which is to say: while historically some of these values were in tension (i.e., making software more expressive might implicitly be making it less robust or more poorly performing), through innovation Rust is finding solutions that don’t compromise one of these values for the sake of the other.

2. The macros are incredible

When I was first learning C, I was (rightly) warned against using the C preprocessor. But like many of the things that we are cautioned about in our youth, this warning was one that the wise give to the enthusiastic to prevent injury; the truth is far more subtle. And indeed, as I came of age as a C programmer, I not only came to use the preprocessor, but to rely upon it. Yes, it needed to be used carefully — but in the right hands it could generate cleaner, better code. (Indeed, the preprocessor is very core to the way we implement DTrace’s statically defined tracing.) So if anything, my problems with the preprocessor were not its dangers so much as its many limitations: because it is, in fact, a preprocessor and not built into the language, there were all sorts of things that it would never be able to do — like access the abstract syntax tree.

With Rust, I have been delighted by its support for hygienic macros. This not only solves the many safety problems with preprocessor-based macros, it allows them to be outrageously powerful: with access to the AST, macros are afforded an almost limitless expansion of the syntax — but invoked with an indicator (a trailing bang) that makes it clear to the programmer when they are using a macro. For example, one of the fully worked examples in Programming Rust is a json! macro that allows for JSON to be easy declared in Rust. This gets to the ergonomics of Rust, and there are many macros (e.g., format!, vec!, etc.) that make Rust more pleasant to use.

Another advantage of macros: they are so flexible and powerful that they allow for effective experimentation. For example, the propagation operator that I love so much actually started life as a try! macro; that this macro was being used ubiquitously (and successfully) allowed a language-based solution to be considered. Languages can be (and have been!) ruined by too much experimentation happening in the language rather than in how it’s used; through its rich macros, it seems that Rust can enable the core of the language to remain smaller — and to make sure that when it expands, it is for the right reasons and in the right way.

3. format! is a pleasure

Okay, this is a small one but it’s (another) one of those little pleasantries that has made Rust really enjoyable. Many (most? all?) languages have an approximation or equivalent of the venerable sprintf, whereby variable input is formatted according to a format string. Rust’s variant of this is the format! macro (which is in turn invoked by println!, panic!, etc.), and (in keeping with one of the broader themes of Rust) it feels like it has learned from much that came before it. It is type-safe (of course) but it is also clean in that the {} format specifier can be used on any type that implements the Display trait. I also love that the {:?} format specifier denotes that the argument’s Debug trait implementation should be invoked to print debug output. More generally, all of the format specifiers map to particular traits, allowing for an elegant approach to an historically grotty problem. There are a bunch of other niceties, and it’s all a concrete example of how Rust uses macros to deliver nice things without sullying syntax or otherwise special-casing. None of the formatting capabilities are unique to Rust, but that’s the point: in this (small) domain (as in many) Rust feels like a distillation of the best work that came before it. As anyone who has had to endure one of my talks can attest, I believe that appreciating history is essential both to understand our present and to map our future. Rust seems to have that perspective in the best ways: it is reverential of the past without being incarcerated by it.

4. include_str! is a godsend

One of the filthy aspects of the statemap code is that it is effectively encapsulating another program — a JavaScript program that lives in the SVG to allow for the interactivity of the statemap. This code lives in its own file, which the statemap code should pass through to the generated SVG. In the node.js/C hybrid, I am forced to locate the file in the filesystem — which is annoying because it has to be delivered along with the binary and located, etc. Now Rust — like many languages (including ES6) — has support for raw-string literals. As an aside, it’s interesting to see the discussion leading up to its addition, and in particular, how a group of people really looked at every language that does this to see what should be mimicked versus what could be improved upon. I really like the syntax that Rust converged on: r followed by one or more octothorpes followed by a quote to begin a raw string literal, and a quote followed by a matching number of octothorpes followed to end a literal, e.g.:

let str = r##""What a curious feeling!" said Alice"##;

This alone would have allowed me to do what I want, but still a tad gross in that it’s a bunch of JavaScript living inside a raw literal in a .rs file. Enter include_str!, which allows me to tell the compiler to find the specified file in the filesystem during compilation, and statically drop it into a string variable that I can manipulate:

...

/*

* Now drop in our in-SVG code.

*/

let lib = include_str!("statemap-svg.js");

...

So nice! Over the years I have wanted this many times over for my C, and it’s another one of those little (but significant!) things that make Rust so refreshing.

5. Serde is stunningly good

Serde is a Rust crate that allows for serialization and deserialization, and it’s just exceptionally good. It uses macros (and, in particular, Rust’s procedural macros) to generate structure-specific routines for serialization and deserialization. As a result, Serde requires remarkably little programmer lift to use and performs eye-wateringly well — a concrete embodiment of Rust’s repeated defiance of the conventional wisdom that programmers must choose between abstractions and performance!

For example, in the statemap implementation, the input is concatenated JSON that begins with a metadata payload. To read this payload in Rust, I define the structure, and denote that I wish to derive the Deserialize trait as implemented by Serde:

#[derive(Deserialize, Debug)]

#[allow(non_snake_case)]

struct StatemapInputMetadata {

start: Vec<u64>,

title: String,

host: Option<String>,

entityKind: Option<String>,

states: HashMap<String, StatemapInputState>,

}

Then, to actually parse it:

let metadata: StatemapInputMetadata = serde_json::from_str(payload)?;

That’s… it. Thanks to the magic of the propagation operator, the errors are properly handled and propagated — and it has handled tedious, error-prone things for me like the optionality of certain members (itself beautifully expressed via Rust’s ubiquitous Option type). With this one line of code, I now (robustly) have a StatemapInputMetadata instance that I can use and operate upon — and this performs incredibly well on top of it all. In this regard, Serde represents the best of software: it is a sophisticated, intricate implementation making available elegant, robust, high-performing abstractions; as legendary White Sox play-by-play announcer Hawk Harrelson might say, MERCY!

6. I love tuples

In my C, I have been known to declare anonymous structures in functions. More generally, in any strongly typed language, there are plenty of times when you don’t want to have to fill out paperwork to be able to structure your data: you just want a tad more structure for a small job. For this, Rust borrows an age-old construct from ML in tuples. Tuples are expressed as a parenthetical list, and they basically work as you expect them to work in that they are static in size and type, and you can index into any member. For example, in some test code that needs to make sure that names for colors are correctly interpreted, I have this:

let colors = vec![

("aliceblue", (240, 248, 255)),

("antiquewhite", (250, 235, 215)),

("aqua", (0, 255, 255)),

("aquamarine", (127, 255, 212)),

("azure", (240, 255, 255)),

/* ... */

];

Then colors[2].0 (say) which will be the string “aqua”; (colors[1].1).2 will be the integer 215. Don’t let the absence of a type declaration in the above deceive you: tuples are strongly typed, it’s just that Rust is inferring the type for me. So if I accidentally try to (say) add an element to the above vector that contains a tuple of mismatched signature (e.g., the tuple “((188, 143, 143), ("rosybrown"))“, which has the order reversed), Rust will give me a compile-time error.

The full integration of tuples makes them a joy to use. For example, if a function returns a tuple, you can easily assign its constituent parts to disjoint variables, e.g.:

fn get_coord() -> (u32, u32) {

(1, 2)

}

fn do_some_work() {

let (x, y) = get_coord();

/* x has the value 1, y has the value 2 */

}

Great stuff!

7. The integrated testing is terrific

One of my regrets on DTrace is that we didn’t start on the DTrace test suite at the same time we started the project. And even after we starting building it (too late, but blessedly before we shipped it), it still lived away from the source for several years. And even now, it’s a bit of a pain to run — you really need to know it’s there.

This represents everything that’s wrong with testing in C: because it requires bespoke machinery, too many people don’t bother — even when they know better! Viz.: in the original statemap implementation, there is zero testing code — and not because I don’t believe in it, but just because it was too much work for something relatively small. Yes, there are plenty of testing frameworks for C and C++, but in my experience, the integrated frameworks are too constrictive — and again, not worth it for a smaller project.

With the rise of test-driven development, many languages have taken a more integrated approach to testing. For example, Go has a rightfully lauded testing framework, Python has unittest, etc. Rust takes a highly integrated approach that combines the best of all worlds: test code lives alongside the code that it’s testing — but without having to make the code bend to a heavyweight framework. The workhorses here are conditional compilation and Cargo, which together make it so easy to write tests and run them that I found myself doing true test-driven development with statemaps — namely writing the tests as I develop the code.

8. The community is amazing

In my experience, the best communities are ones that are inclusive in their membership but resolute in their shared values. When communities aren’t inclusive, they stagnate, or rot (or worse); when communities don’t share values, they feud and fracture. This can be a very tricky balance, especially when so many open source projects start out as the work of a single individual: it’s very hard for a community not to reflect the idiosyncrasies of its founder. This is important because in the open source era, community is critical: one is selecting a community as much as one is selecting a technology, as each informs the future of the other. One factor that I value a bit less is strictly size: some of my favorite communities are small ones — and some of my least favorite are huge.

For purposes of a community, Rust has a luxury of clearly articulated, broadly shared values that are featured prominently and reiterated frequently. If you head to the Rust website this is the first sentence you’ll read:

Rust is a systems programming language that runs blazingly fast, prevents segfaults, and guarantees thread safety.

That gets right to it: it says that as a community, we value performance and robustness — and we believe that we shouldn’t have to choose between these two. (And we have seen that this isn’t mere rhetoric, as so many Rust decisions show that these values are truly the lodestar of the project.)

And with respect to inclusiveness, it is revealing that you will likely read that statement of values in your native tongue, as the Rust web page has been translated into thirteen languages. Just the fact that it has been translated into so many languages makes Rust nearly unique among its peers. But perhaps more interesting is where this globally inclusive view likely finds its roots: among the sites of its peers, only Ruby is similarly localized. Given that several prominent Rustaceans like Steve Klabnik and Carol Nichols came from the Ruby community, it would not be unreasonable to guess that they brought this globally inclusive view with them. This kind of inclusion is one that one sees again and again in the Rust community: different perspectives from different languages and different backgrounds. Those who come to Rust bring with them their experiences — good and bad — from the old country, and the result is a melting pot of ideas. This is an inclusiveness that runs deep: by welcoming such disparate perspectives into a community and then uniting them with shared values and a common purpose, Rust achieves a rich and productive heterogeneity of thought. That is, because the community agrees about the big things (namely, its fundamental values), it has room to constructively disagree (that is, achieve consensus) on the smaller ones.

Which isn’t to say this is easy! Check out Ashley Williams in the opening keynote from RustConf 2018 for how exhausting it can be to hash through these smaller differences in practice. Rust has taken a harder path than the “traditional” BDFL model, but it’s a qualitatively better one — and I believe that many of the things that I love about Rust are a reflection of (and a tribute to) its robust community.

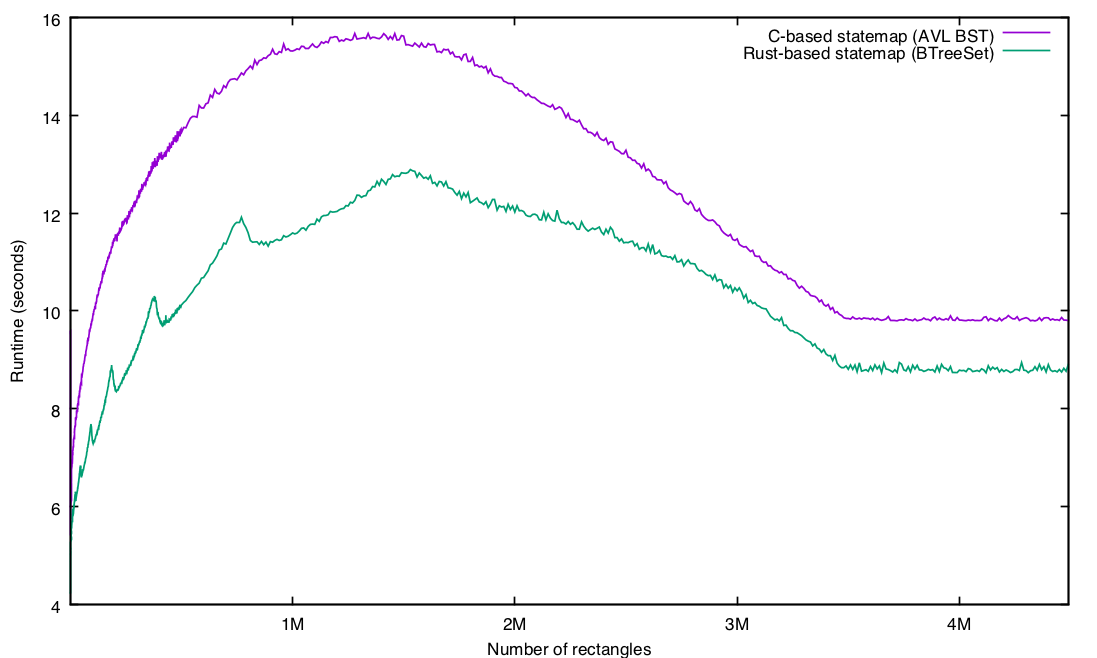

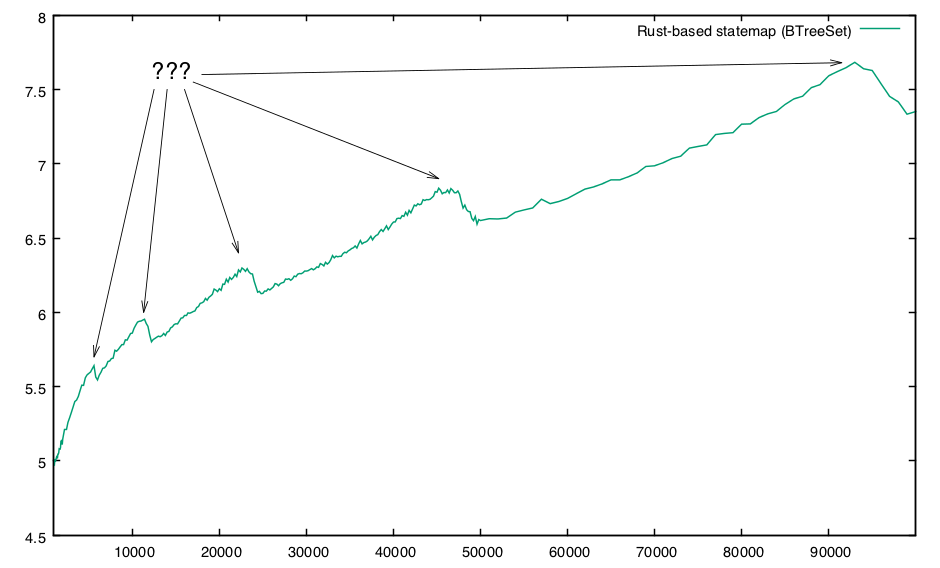

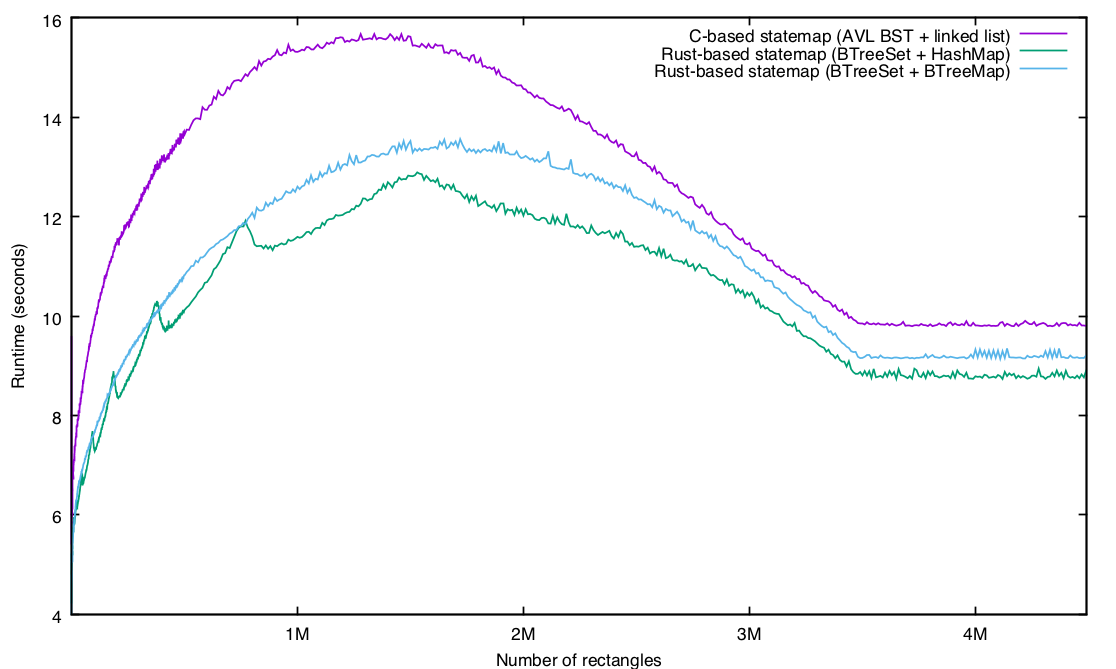

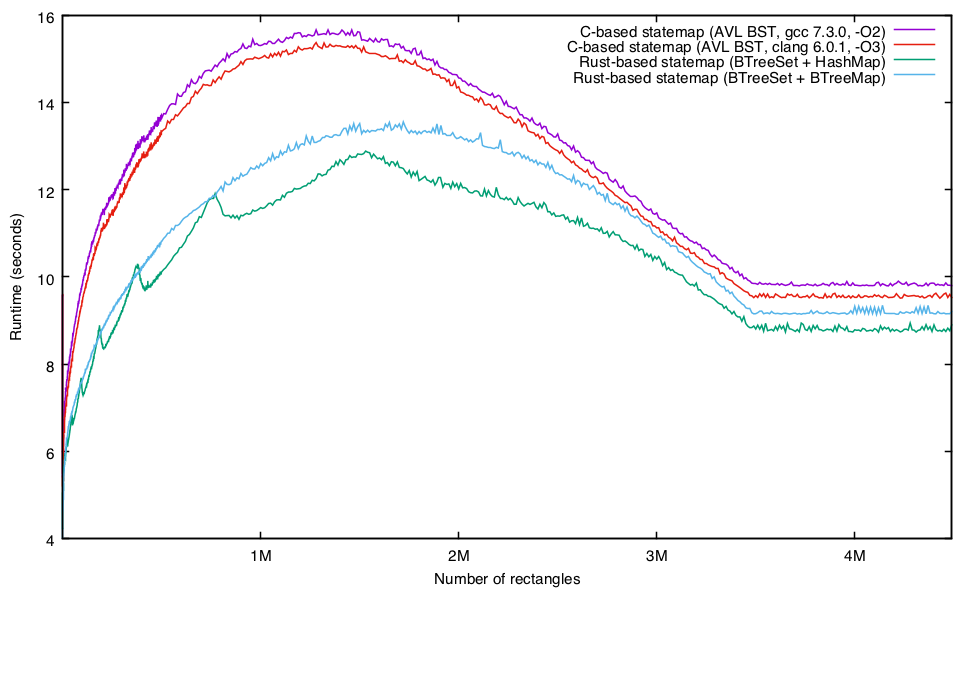

9. The performance rips

Finally, we come to the last thing I discovered in my Rust odyssey — but in many ways, the most important one. As I described in an internal presentation, I had experienced some frustrations trying to implement in Rust the same structure I had had in C. So I mentally gave up on performance, resolving to just get something working first, and then optimize it later.

I did get it working, and was able to benchmark it, but to give some some context for the numbers, here is the time to generate a statemap in the old (slow) pure node.js implementation for a modest trace (229M, ~3.9M state transitions) on my 2.9 GHz Core i7 laptop:

% time ./statemap-js/bin/statemap ./pg-zfs.out > js.svg

real 1m23.092s

user 1m21.106s

sys 0m1.871s

This is bad — and larger input will cause it to just run out of memory. And here’s the version as reimplemented as a C/node.js hybrid:

% time ./statemap-c/bin/statemap ./pg-zfs.out > c.svg

real 0m11.800s

user 0m11.414s

sys 0m0.330s

This was (as designed) a 10X improvement in performance, and represents speed-of-light numbers in that this seems to be an optimal implementation. Because I had written my Rust naively (and my C carefully), my hope was that the Rust would be no more than 20% slower — but I was braced for pretty much anything. Or at least, I thought I was; I was actually genuinely taken aback by the results:

$ time ./statemap.rs/target/release/statemap ./pg-zfs.out > rs.svg

3943472 records processed, 24999 rectangles

real 0m8.072s

user 0m7.828s

sys 0m0.186s

Yes, you read that correctly: my naive Rust was ~32% faster than my carefully implemented C. This blew me away, and in the time since, I have spent some time on a real lab machine running SmartOS (where I have reproduced these results and been able to study them a bit). My findings are going to have to wait for another blog entry, but suffice it to say that despite executing a shockingly similar number of instructions, the Rust implementation has a different load/store mix (it is much more store-heavy than C) — and is much better behaved with respect to the cache. Given the degree that Rust passes by value, this makes some sense, but much more study is merited.

It’s also worth mentioning that there are some easy wins that will make the Rust implementation even faster: after I had publicized the fact that I had a Rust implementation of statemaps working, I was delighted when David Tolnay, one of the authors of Serde, took the time to make some excellent suggestions for improvement. For a newcomer like me, it’s a great feeling to have someone with such deep expertise as David’s take an interest in helping me make my software perform even better — and it is revealing as to the core values of the community.

Rust’s shockingly good performance — and the community’s desire to make it even better — fundamentally changed my disposition towards it: instead of seeing Rust as a language to augment C and replace dynamic languages, I’m looking at it as a language to replace both C and dynamic languages in all but the very lowest layers of the stack. C — like assembly — will continue to have a very important place for me, but it’s hard to not see that place as getting much smaller relative to the barnstorming performance of Rust!

Beyond the first impressions

I wouldn’t want to imply that this is an exhaustive list of everything that I have fallen in love with about Rust. That list is much longer would include at least the ownership model; the trait system; Cargo; the type inference system. And I feel like I have just scratched the surface; I haven’t waded into known strengths of Rust like the FFI and the concurrency model! (Despite having written plenty of multithreaded code in my life, I haven’t so much as created a thread in Rust!)

Building a future

I can say with confidence that my future is in Rust. As I have spent my career doing OS kernel development, a natural question would be: do I intend to rewrite the OS kernel in Rust? In a word, no. To understand my reluctance, take some of my most recent experience: this blog entry was delayed because I needed to debug (and fix) a nasty problem with our implementation of the Linux ABI. As it turns out, Linux and SmartOS make slightly different guarantees with respect to the interaction of vfork and signals, and our code was fatally failing on a condition that should be impossible. Any old Unix hand (or quick study!) will tell you that vfork and signal disposition are each semantic superfund sites in their own right — and that their horrific (and ill-defined) confluence can only be unimaginably toxic. But the real problem is that actual software implicitly depends on these semantics — and any operating system that is going to want to run existing software will itself have to mimic them. You don’t want to write this code, because no one wants to write this code.

Now, one option (which I honor!) is to rewrite the OS from scratch, as if legacy applications essentially didn’t exist. While there is a tremendous amount of good that can come out of this (and it can find many use cases), it’s not a fit for me personally.

So while I may not want to rewrite the OS kernel in Rust, I do think that Rust is an excellent fit for much of the broader system. For example, at the recent OpenZFS Developers Summit, Matt Ahrens and I were noodling the notion of user-level components for ZFS in Rust. Specifically: zdb is badly in need of a rewrite — and Rust would make an excellent candidate for it. There are many such examples spread throughout ZFS and the broader the system, including a few in kernel. Might we want to have a device driver model that allows for Rust drivers? Maybe! (And certainly, it’s technically possible.) In any case, you can count on a lot more Rust from me and into the indefinite future — whether in the OS, near the OS, or above the OS.

Taking your own plunge

I wrote all of this up in part to not only explain why I took the plunge, but to encourage others to take their own. If you were as I was and are contemplating diving into Rust, a couple of pieces of advice, for whatever they’re worth:

- I would recommend getting both The Rust Programming Language and Programming Rust. They are each excellent in their own right, and different enough to merit owning both. I also found it very valuable to have two different sources on subjects that were particularly thorny.

- Understand ownership before you start to write code. The more you understand ownership in the abstract, the less you’ll have to learn at the merciless hands of compiler error messages.

- Get in the habit of running rustc on short programs. Cargo is terrific, but I personally have found it very valuable to write short Rust programs to understand a particular idea — especially when you want to understand optional or new features of the compiler. (Roll on, non-lexical lifetimes!)

- Be careful about porting something to Rust as a first project — or otherwise implementing something you’ve implemented before. Now, obviously, this is exactly what I did, and it can certainly be incredibly valuable to be able to compare an implementation in Rust to an implementation in another language — but it can also cut against you: the fact that I had implemented statemaps in C sent me down some paths that were right for C but wrong for Rust; I made much better progress when I rethought the implementation of my problem the way Rust wanted me to think about it.

- Check out the New Rustacean podcast by Chris Krycho. I have really enjoyed Chris’s podcasts, and have been working my way through them when commuting or doing household chores. I particularly enjoyed his interview with Sean Griffen and his interview with Carol Nichols.

- Check out rustlings. I learned about this a little too late for me; I wish I had known about it earlier! I did work through the Rust koans, which I enjoyed and would recommend for the first few hours with Rust.

I’m sure that there’s a bunch of stuff that I missed; if there’s a particular resource that you found useful when learning Rust, message me or leave a comment here and I’ll add it.

Let me close by offering a sincere thanks to those in the Rust community who have been working so long to develop such a terrific piece of software — and especially those who have worked so patiently to explain their work to us newcomers. You should be proud of what you’ve accomplished, both in terms of a revolutionary technology and a welcoming community — thank you for inspiring so many of us about what infrastructure software can become, and I look forward to many years of implementing in Rust!