The Economics of Software

Software is like nothing else in the history of human endeavor:1 unlike everything else we have ever built, software costs nothing to manufacture, and it never wears out. Yet these magical properties are arguably overshadowed by the ugly truth that software remains incredibly expensive to build. This gives rise to some strange economic properties: software’s fixed costs are high (very high – too high), but its variable costs are zero. As strange as they are, these economic properties aren’t actually unique to software; they are also true (to varying degree) of the products that we have traditionally called “intellectual property.” But unlike books or paintings or movies, software is predominantly an industrial good – it is almost always used as a component in a larger, engineered system. When you take these together – software’s role as an industrial good, coupled with its high fixed costs and zero variable costs – you get all sorts of strange economic phenomena. For example, doesn’t it strike you as odd that your operating system is essentially free, but your database is still costing you forty grand per CPU? Is a database infinitely more difficult to write than an operating system? (Answer: no.) If not, why the enormous pricing discrepancy?

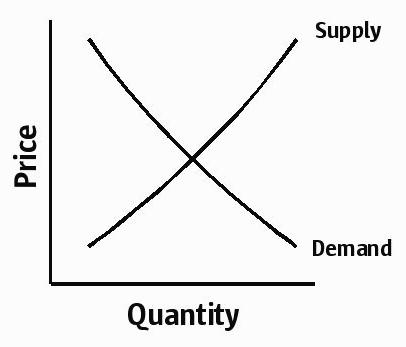

I want to ultimately address the paradox of the software price discrepancy, but first a quick review of the laws of supply and demand in a normal market: at high prices, suppliers tend to want to supply more, while consumers tend to demand less; at low prices, consumers tend to demand more, while suppliers tend to want to supply less. We can show price versus quantity demanded/supplied with the classic supply and demand curves:

The point of intersection of the curves is the equilibrium price, and the laws of supply and demand tend to keep the market in equilibrium: as prices rise slightly out of equilibrium, suppliers will supply a little more, consumers will demand a little less, inventories will rise a little bit, and prices will fall back into equilibrium. Likewise, if prices fall slightly, consumers will demand a little more, inventories will become depleted, and prices will rise back into equilibrium.

The degree to which suppliers and consumers can react to prices – the slope of their respective curve – is known as price elasticity. In a price inelastic market, suppliers or consumers cannot react quickly to prices. For example, cigarettes have canonically high inelastic demand: if prices increase, few smokers will quit. (That said, demand for a particular brand of cigarettes is roughly normal: if Marlboros suddenly cost ten bucks a pack, cheap Russian imports may begin to look a lot more attractive.)

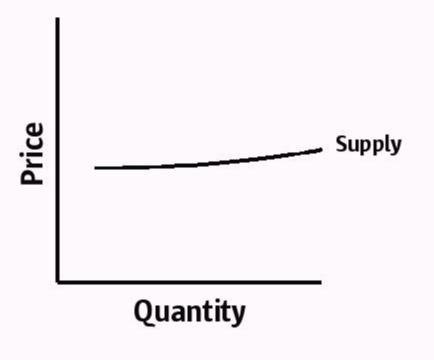

So that’s the market for smokes, but what of software? Let’s start by looking at the supply side, because it’s pretty simple: the zero variable cost means that suppliers can supply an arbitrary quantity at a given price. That is, this is the supply curve for software:

The height of the “curve” will be dictated by various factors: competitive environment, fixed costs, etc.; we’ll talk about how the height of this curve is set (and shifted) in a bit.

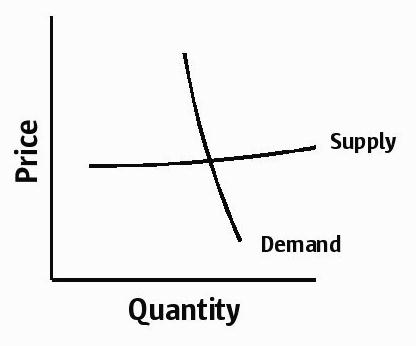

And what of the demand side? Software demand is normal to the degree that consumers have the freedom to choose software components. The problem is that for all of the rhetoric about software becoming a “commodity”, most software is still very much not a commodity: one software product is rarely completely interchangeable with another. The lack of interchangeability isn’t as much of an issue for a project that is still being specified (one can design around the specific intricacies of a specific piece of software), but it’s very much an issue after a project has deployed: deployed systems are rife with implicit dependencies among the different software components. These dependencies – and thus the cost to replace a given software component – tend to increase over time. That is, your demand becomes more and more price inelastic as time goes on, until you reach a point of complete price inelasticity. Perhaps this is the point when you have so much layered on top of the decision, that a change is economically impossible. Or perhaps it’s the point when the technical talent that would retool your infrastructure around a different product has gone on to do something else – or perhaps they’re no longer with the company. Whatever the reason, it’s the point after which the software has become so baked into your infrastructure, the decision cannot be revisited.

So instead of looking the nice supply and demand curves above, software supply and demand curves tend to look like this:

And of course, your friendly software vendor knows that your demand tends towards inelasticity – which is why they so frequently raise the rent while offering so little in return. We’ve always known about this demand inelasticity, we’ve just called it something else: vendor lock-in.

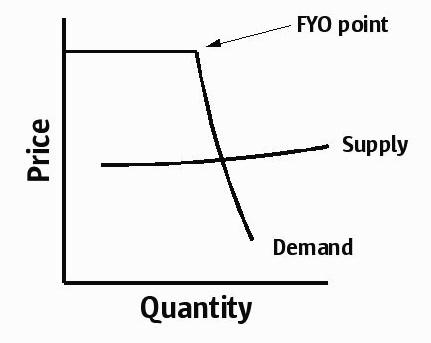

If software suppliers have such unbelievable pricing power, why don’t companies end up forking over every last cent for software? Because the demand for software isn’t completely price inelastic. It’s only inelastic as long as the price is below the cost of switching software. In the spirit of the FYO billboard on the 101, I dub this switching point the “FYO point”: it is the point at which you get so pissed off at your vendor that you completely reevaluate your software decision – you put everything back on the table. So here’s the completed picture:

What happens at the FYO point? In extreme cases, you may decide to rewrite it yourself. Or maybe you’ll decide that it’s worth the pain to switch to a different (and less rapacious) vendor – or at least scaring your existing vendor to ease up a bit on their pricing. Or maybe you’ll ramp up a new project to replace the existing one, using all new components – thus normalizing your demand curve. And increasingly often, you decide that you’re not using half of the features of this thing anyway – and you start looking for a “good enough” open source option to get out of this ugly mess once and for all. (More on this later.)

Now, your software vendor doesn’t actually want you to hit the FYO point; they want to keep you far enough below it that you just sigh (or groan) and sign the check. (Which most of them are pretty good at, by the way – but of course, you already know that from all of your sighing and groaning.) There are essentially two ways for a software company to grow revenue on an established software product:

- Take away business from competitors

- Extract more dough out of existing customers

In terms of the FYO point, taking away competitors’ business amounts to lowering the FYO point of competitors’ customers. This can be done through technology (for example, by establishing open standards or developing migration tools) or it can be done through pricing (for example, by lowering the price they charge their competitors’ customers for their software – the “competitive upgrade”). This is a trend that generally benefits customers. If only there were no other option…

Sadly, there is another option, and most software companies opt for it: extracting more money from their existing customers. In terms of the FYO point, this amounts to raising the FYO point of their own customers. That is, software vendors act as a natural monopolist does: focusing their efforts not on competition, but rather on raising barriers to entry. They have all sorts of insidious ways of doing this: proprietary data formats, complicated interdependencies, deliberate incompatibilities, etc. Personally, I find these behaviors abhorrent, and I have been amazed about how brazen some software vendors are about maintaining their inalienable right to screw their own customers. To wit: I now have had not one but two software vendors tell me that I must add a way to disable DTrace for their app to prevent their own customers from observing their software. They’re not even worried about their competitors – they’re too busy screwing their own customers! (Needless to say, their requests for such a feature were, um, declined.)

So how does open source fit into this? Open source is a natural consequence of the economics of software, on both the demand-side and the supply-side. The demand-side has been discussed ad nauseum (and frequently, ad hominem): the demand for open source comes from customers who are sick of their vendors’ unsavory tactics to raise their FYO point – and they are sick more generally of the whole notion of vendor lock-in. The demand-side is generally responsible for customers writing their own software and making it freely available, or participating in similar projects in the community at large. To date, the demand-side has propelled much of open source software, including web servers (Apache) and scripting languages (Perl, Python). With some exception, the demand-side consists largely of individuals participating out of their interest more than their self-interest. As a result, it generally cannot sustain full-time, professional software developers.

But there’s also a supply-side to open source: if software has no variable cost, software companies’ attempts to lower their competitors’ customers’ FYO point will ultimately manifest itself in free software. And the most (if not the only) way to make software convincingly free is to make the source code freely available – to make it open source.2 The tendency towards open source is especially strong when companies profit not directly from the right-to-use of the software, but rather from some complementary good: support, services, other software, or even hardware. (In the specific case of Solaris and Sun, it’s actually all of the above.) And what if customers never consume any of these products? Well, the software costs nothing to manufacture, so there isn’t a loss – and there is often an indirect gain. To take the specific example of Solaris: if you run Solaris and never give a nickel to Sun, that’s fine by us; it didn’t even cost us a nickel to make your copy, and your use will increase the market for Solaris applications and solutions – driving platform adoption and ultimately driving revenue for Sun. To put this in retail terms, open source software has all of the properties of a loss-leader – minus the loss, of course.

While the demand-side has propelled much of open source to date, the supply-side is (in my opinion) ultimately a more powerful force in the long run: the software created by supply-side forces is generally been developed by people who do it full-time for a living – there is naturally a greater attention to detail. For a good example of supply-side forces, look at operating systems where Linux – the traditionally dominant open source operating system – has enjoyed profound benefits from the supply-side. These include contributions from operating systems such as AIX (JFS, scalability work), IRIX (XFS, observability tools and the occasional whoopsie), DYNIX/ptx (RCU locks), and even OS/2 (DProbes). And an even larger supply-side contribution looms: the open sourcing of Solaris. This will certainly be the most important supply-side contribution to date, and a recognition of the economics both of the operating systems market and of the software market more generally. And unlike much prior supply-side open source activity, the open sourcing of Solaris is not open source as capitulation – it is open source as counter-strike.

To come back to our initial question: why is the OS basically free while the database is costing you forty grand per CPU? The short answer is that the changes that have swept through the enterprise OS market are still ongoing in the database market. Yes, there have been traditional demand-side efforts like MySQL and research efforts like PostgreSQL, but neither of these “good enough” efforts has actually been good enough to compete with Informix, Oracle, DB/2 or Sybase in the enterprise market. In the last few years, however, we have seen serious supply-side movement, with MaxDB from SAP and Ingres from CA both becoming open source. Will either of these be able to start taking serious business away from Oracle and IBM? That is, will they be enough to lower the FYO point such that more customers say “FY, O”? The economics of software tells us that, in the long run, this is likely the case: either the demand-side will ultimately force sufficient improvements to the existing open source databases, or the supply-side will force the open sourcing of one of the viable competitors. And that software does not wear out and costs nothing to manufacture assures us that the open source databases will survive to stalk their competitors into the long run. Will this happen anytime soon? As Keynes famously pointed out, “in the long run, we are all dead” – so don’t count on any less sighing or groaning or check writing in the immediate future…

-

As an aside, I generally hate this rhetorical technique of saying that “[noun] is the [superlative] [same noun] [verb] by humankind.” It makes it sound like the chimps did this years ago, but we humans have only recently caught up. I regret using this technique myself, so let me clarify: with the notable exception of gtik2_applet2, the chimps have not yet discovered how to write software. ↩︎

-

Just to cut off any rabid comments about definitions: by “open source” I only mean that the source code is sufficiently widely and publicly available that customers don’t question that its right-to-use is (and will always be) free. This may or may not mean OSI-approved, and it may or may not mean GPL. And of course, many customers have discovered that open source alone doesn’t solve the problem. You need someone to support it – and the company offering support begins to look, act and smell a lot like a traditional, rapacious software company. (Indeed, FYO point may ultimately be renamed the “FYRH point.”) You still need open standards, open APIs, portable languages and so on… ↩︎